Scott A. Boruchow, MD, And Christopher H. Gibbons, MD, MMSc

Autonomic and Peripheral Nerve Laboratory, Department of Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 1 Deaconess Road, Boston, Massachusetts, 02215, USA

Accepted 24 March 2013

ABSTRACT:

Introduction: We examined the role of skin biopsy in the evaluation and management of patients with suspected small fiber neuropathy (SFN). Methods: A retrospective chart review was performed among all patients who underwent skin biopsy for evaluation of SFN at our institution between March 2008 and March 2011. Change in management was defined as a new diagnosis or change in treatment in response to both positive and negative skin biopsies. Results: Among 69 patients who underwent skin biopsy, 25 had pathological evidence of an SFN, and 9 had evidence of borderline SFN. Change in management or diagnosis occurred in 14 of 25 patients with definite SFN, 6 of 9 patients with borderline SFN, and 16 of 35 biopsy negative patients. Conclusions: Skin biopsy changed management or diagnosis in 52% of patients evaluated for a possible SFN and appears to play a valuable role in the workup of these patients.

It is common in clinical practice to encounter patients who present with symptoms of burning, tingling, or shooting pain in the toes and have minimal findings on neurological examination. A diagnosis of small-fiber neuropathy should be considered in this setting, but confirmation is difficult due to subtle physical examination findings and normal routine electrodiagnostic testing.1–4 A selective small fiber neuropathy occurs when damage to the peripheral nerves predominately involves the small myelinated A-delta fibers or unmyelinated C fibers; this finding is supported by morphologic changes to nerve fibers on skin biopsy and is confirmed with a reduction of the intra-epidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD).2,5–7

The sensitivity (74–90%) and specificity (64– 90%) of skin biopsy for diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy is high across all studies.8–11 Consensus guidelines have found skin biopsy to be more sensitive than quantitative sensory testing, and both are more sensitive and less invasive than sural nerve biopsy.6,12 Skin biopsy establishes a diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy, thereby prompting the physician to search for the underlying etiology.13–15 Alternatively, if clinical suspicion for small fiber neuropathy is low and skin biopsy shows normal IENFD with no morphologic changes suggestive of ongoing damage, the biopsy may lower the likelihood of a diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. This may thereby limit unnecessary and costly investigations. The goal of this study is to examine the role of skin biopsy in the evaluation and management of patients with possible small fiber neuropathy.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review was performed in all patients who underwent skin biopsy for evaluation of possible small fiber neuropathy at our institution between March 2008 and March 2011, with approval of the Beth Israel Deaconess Institutional Review Board. All patients were required to have signs or symptoms that could be consistent with small-fiber neuropathy and a history and physical examination documented by a neurologist at our institution. History, physical examination, laboratory, and biopsy results were obtained by means of chart review. The data collector was blinded to the skin biopsy results when data were extracted from the chart. In cases when multiple neurological assessments were performed, the examination closest to the date of the biopsy was used. When differing examinations were present, the results of the most experienced examiner were chosen (i.e., neuromuscular or peripheral nerve specialist more than general neurologist or neuromuscular attending more than neuromuscular fellow). Missing data were imputed as being absent (i.e., if hyperalgesia or allodynia were not discussed, they were assumed to be absent).

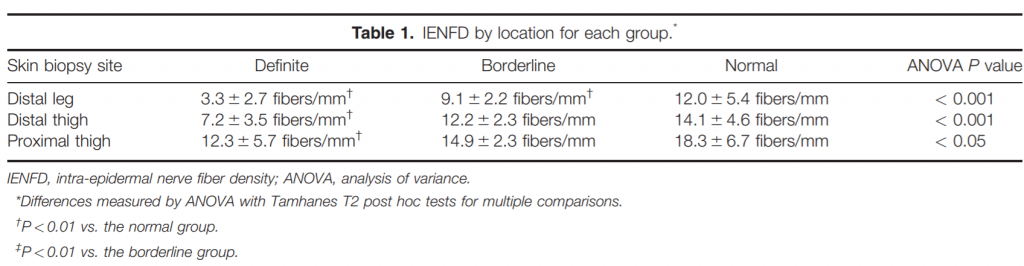

Three-millimeter punch biopsies were obtained from the right leg 10 cm above the lateral malleolus, 10 cm above the lateral knee, and 10 cm below the hip to the depth of the subcutaneous fat using standard techniques and locations.1,2 The specimens were placed in Zamboni fixative and underwent standard PGP9.5 immunostaining with 50 micrometer sections. IENFD at proximal thigh, distal thigh, and distal leg were recorded and compared with normal values for our laboratory: 5 fibers/mm in the distal leg, 7 fibers/mm in the distal thigh, and 8 fibers/mm in the proximal thigh. In addition, morphological changes such as axon swelling or branching were noted.

Individuals were divided into 3 categories: definite small fiber neuropathy, borderline small fiber neuropathy, or no small fiber neuropathy based on their clinical and pathological findings.16 Individuals with reduced IENFD at 1 or more sites were given a diagnosis of definite small fiber neuropathy. Individuals with a high clinical suspicion of small fiber neuropathy based on the presence of painful distal symptoms and at least 1 abnormal exam finding (thermal or pinprick loss) and with IENFD in the low normal range (5–7 fibers/mm in the distal leg) were given a diagnosis of borderline small fiber neuropathy. In addition, if individuals had morphologic changes (swellings or branching) but did not otherwise meet criteria for definite SFN, they were placed in the borderline SFN category. All others were given a diagnosis of no small fiber neuropathy. We also examined the utility of performing 3 skin biopsies in these individuals.

The study was reviewed as intention to treat, thus outcome data are reported out of the original 69 cases. Data in the text are reported as mean6 standard deviation, range of values or absolute numbers with percent, as appropriate. Differences between groups (continuous data) were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tamhanes T2 post hoc tests. Symptoms and exam findings with binary responses (i.e., present or absent) were compared using the Freeman-Halton extension of the Fisher exact test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Because of the exploratory nature of the study, Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons were not performed.

RESULTS

Demographics. Among 69 eligible individuals who underwent skin biopsy, 68 had data sufficient for study, with 1 lost to follow-up. A total of 13 physicians at our institution referred and examined the 69 patients. Six were neuromuscular specialists, 2 were peripheral nerve specialists, and 5 were general neurologists. The average patient age was 47 6 16 years (range, 14–81 years), with 25 men and 44 women.

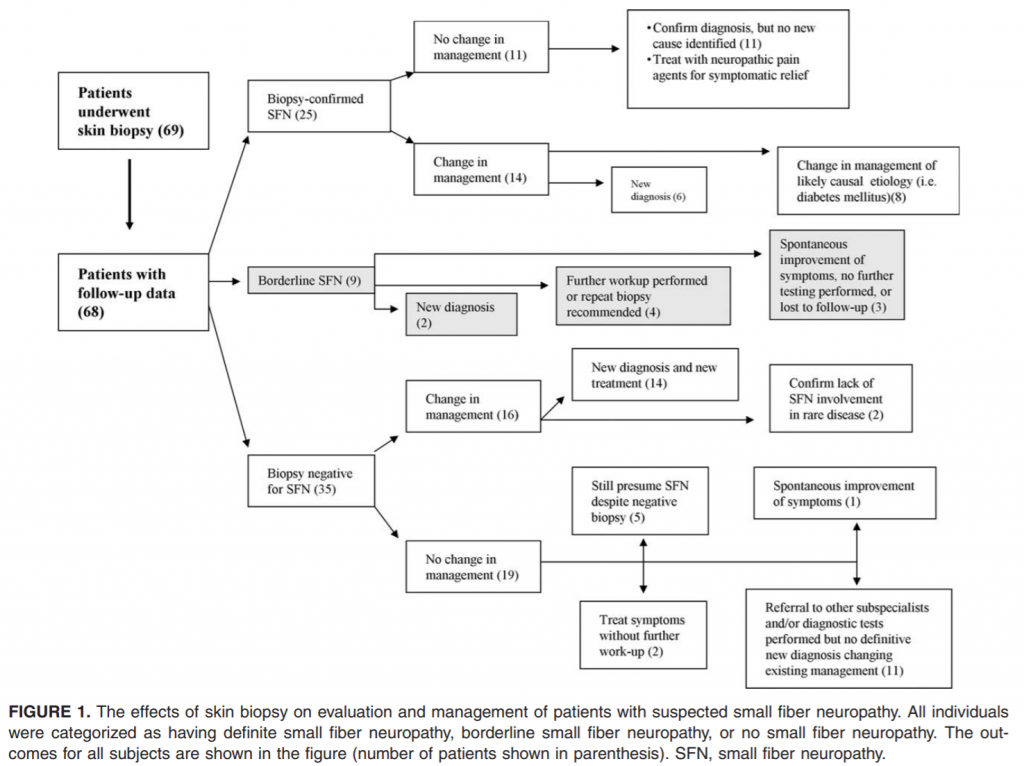

Skin Biopsy Results. Twenty-five patients had reduced IENFD on skin biopsy, confirming a definite small fiber neuropathy. The individuals with definite small fiber neuropathy all had reduced IENFD at the distal leg site in addition to variable reduction in IENFD at more proximal sites. Nine individuals had a diagnosis of borderline small fiber neuropathy, while the remaining 35 individuals had no small fiber neuropathy. Results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Change in Management. A clear change in management occurred in 36 of 69 patients (52%): 14 of 25 with definite small fiber neuropathy, 6 of 9 with borderline small fiber neuropathy, and 16 of 35 patients with no small fiber neuropathy. Of those with definite small fiber neuropathy, 6 of 25 had a new clinical diagnosis identified because of the skin biopsy as outlined in Figure 1. Newly identified diseases included diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance (2), Sjogren syndrome, rheuma- € toid arthritis, and Ross syndrome. Another 8 of 25 with diabetes mellitus had more aggressive management of their diabetes, including insulin, oral hypoglycemic medications, dietary adjustments, exercise, and weight loss counseling. The remaining 11 patients with small fiber neuropathy had no change in management.

As summarized in Figure 1, 6 of 9 patients with borderline small fiber neuropathy had a change in management. Two individuals had a new clinical diagnosis (diabetes mellitus in 1 and impaired glucose tolerance in the other). Four of the patients underwent further laboratory testing as a consequence of the biopsy result and had plans for a follow-up skin biopsy in the future.

Among the 35 patients who had normal skin biopsies 16 had a change in management. Fourteen had new diagnoses or treatments, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy for musculoskeletal pain, orthotics for plantar fasciitis and Morton neuroma, dopamine agonists for restless legs syndrome, epidural steroid injections for lumbar spinal stenosis, calcium-channel blockers for Raynaud syndrome, anti-epileptic drugs for peripheral nerve hyperexcitability syndrome, and biofeedback and mind–body programs for depression. Two patients with a rare autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy had severe dysautonomia and widespread anhidrosis. Both patients had normal skin biopsies, thus there was pathologic confirmation that the disease had not caused permanent postganglionic nerve fiber damage. They, therefore, underwent more aggressive immunotherapy with prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasma exchange. These 2 patients returned to their baseline status over 2 years of intense immunomodulatory therapy, which would not have been given if postganglionic damage were present on skin biopsy.

Among those without a clear change in management, 11 patients were referred to other specialists including rheumatologists, podiatrists, metabolic specialists, orthopedic surgeons, and psychiatrists and/or underwent further diagnostic testing including electromyography with nerve conduction studies (electromyography, EMG), imaging, and laboratory testing after their skin biopsy was negative. Among the remaining 8 biopsy negative patients, 1 had spontaneous resolution of symptoms, aborting further evaluation, and 2 continued to be treated with neuropathic pain medications without further investigation.

Underlying Disorders. These 69 patients had a spectrum of underlying disorders, and the likelihood of skin biopsy abnormality depended on the primary diagnosis. All 7 patients with diabetes mellitus type 1 had a reduction of IENFD. All developed symptoms after rapid improvement in their glucose control, a disorder described as ‘insulin neuritis’ or treatment-induced neuropathy.17 Skin biopsy results were used to monitor the severity of small fiber neuropathy and provide prognostic information.17 Four of the 6 patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 had evidence of a small-fiber neuropathy, and 1 had a borderline small fiber neuropathy. One patient with impaired glucose tolerance had small fiber neuropathy, while the other had a borderline result. Of the 7 patients with Sjogren syndrome, 2 had small fiber neuropathy, 2 had borderline small fiber neuropathy, and 3 did not have evidence of small fiber neuropathy. One of the 4 patients with an abnormal serum protein electrophoresis had evidence of small fiber neuropathy, while an additional patient had borderline small fiber neuropathy.

Only 1 of 13 patients with a history of psychiatric disorders (including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or substance abuse) was found to have evidence of small-fiber neuropathy, although 3 had borderline results. Of the 6 patients with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, 2 had borderline small fiber neuropathy, while the other 4 had no evidence of neuropathy, and all 8 patients with a history of migraine or chronic daily headache had normal skin biopsies. Additionally, all 4 patients with chronic fatigue and both patients with diffuse chronic pain syndromes had no evidence of small-fiber neuropathy. Among the 9 patients classified as having borderline small fiber neuropathy, 6 had underlying diseases that could cause small fiber neuropathy. One had diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypothyroidism, 1 had impaired glucose tolerance, 1 had Sjogren syndrome, 1 had hepatitis C and Sjogren’s syndrome, 1 had celiac disease, and 1 had a monoclonal gammopathy.

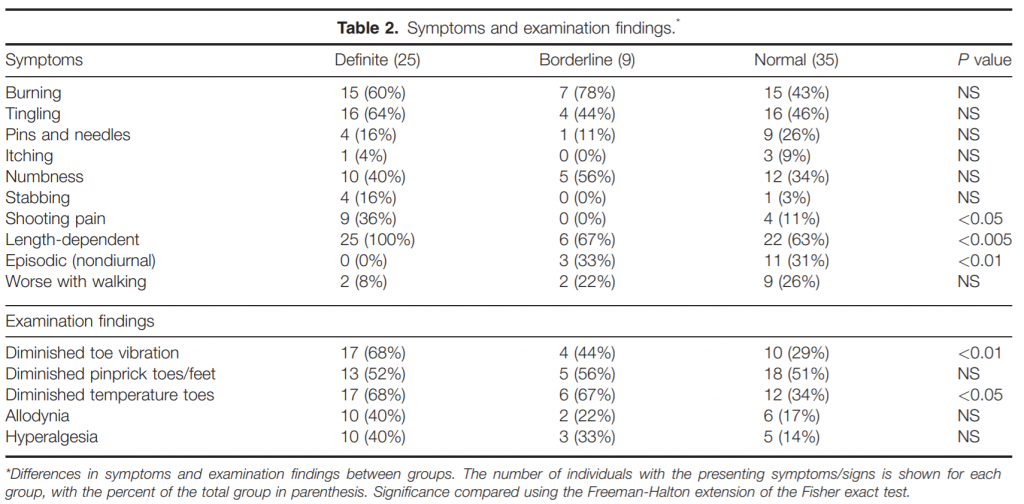

Symptoms and Signs of Small Fiber Neuropathy. Many symptoms typically associated with small fiber neuropathy were found among those with and without pathological evidence on skin biopsy (Table 2). Burning, tingling, pins and needles, numbness, itching, and stabbing pains were commonly reported among all 3 groups. Shooting pain was more common in definite small fiber neuropathy (36%) compared with the other groups. Length dependent symptoms were more common in those with definite small fiber neuropathy, although this was also reported frequently in the borderline and normal groups. Episodic symptoms (defined as nondiurnal periods of pain intermixed with pain-free episodes) were more common in those with normal skin biopsies. Only 2 patients with small fiber neuropathy and 2 patients with borderline small fiber neuropathy had worsening of symptoms with standing or walking, whereas 9 patients without small fiber neuropathy reported this phenomenon (P 5 NS). Examination findings (Table 2) were not effective at distinguishing patients with or without pathologic confirmation of small fiber neuropathy. All patients had normal strength and only age-related decline in reflexes. Diminished temperature and vibration detection in the feet or toes were significantly more common in those with definite small fiber neuropathy, although this was also seen commonly in the other groups. Decreased pinprick sensation in the toes and feet was approximately 50% in all groups.

Utility of Performing 3 Skin Biopsies. In 15 of 69 patients, the most proximal skin biopsy was useful for diagnostic purposes. In 10 of 15 patients, the proximal biopsy site exhibited morphologic abnormalities that suggested an active process with ongoing denervation. Although the distal sites had lower nerve fiber densities consistent with neuropathy, there were no morphologic abnormalities to suggest that the neuropathy was progressing. In 2 of 15 patients, there were no identifiable nerve fibers at the distal leg and distal thigh but relatively normal density at the proximal thigh; this confirmed a severe length-dependent neuropathy and not a ganglionopathy. In 3 of 15 patients, nerve densities were reduced at the proximal thigh but not at distal sites, confirming a non–length-dependent neuropathy.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have reported the sensitivity and specificity of skin biopsy in the investigation of small fiber neuropathy, but few have attempted to determine if skin biopsy changed patient management. Our study demonstrates that 36 of 69 patients (52%) had a definite change in diagnosis or management because of a skin biopsy. Among those individuals with abnormal skin biopsies, over 20% had a new etiology identified for their small fiber neuropathy. Among those with normal skin biopsies, 40% had an alternative diagnosis, often changing management. Many of these patients were returned to their individual institutions for further investigation after a normal skin biopsy. We interpreted unavailable data as negative, which we believe greatly underestimates the percentage of patients whose management was affected by the skin biopsy.

We also noted an unexpected trend in the use of skin biopsies by physicians. Some physicians appeared to use skin biopsies as a way to rule out, rather than rule in, a diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Thus, we suspect that the majority of skin biopsy results, both positive and negative, were of value to the treating physicians in further refining the evaluation and management of patients with suspected small fiber neuropathy. Another recent study found that patients with biopsy-confirmed small fiber neuropathy were twice as likely to respond to neuropathic pain medications compared with those with normal skin biopsies, potentially motivating clinicians to more aggressively identify and treat neuropathic pain in biopsy-proven cases.18

In this cohort of patients, symptoms commonly suggestive of a small-fiber neuropathy such as burning, tingling, and numbness were found in a large percentage of patients with biopsy-confirmed small-fiber neuropathy; however, they were also found in a large percentage of patients without pathologic evidence of neuropathy, thus limiting their positive predictive value. In addition, examination findings did not seem to distinguish effectively between patients with definite or borderline small fiber neuropathy and those without. Although pinprick is frequently identified as abnormal in patients with small fiber neuropathy, we found reduced pin sensitivity in more than half of the patients with and without evidence of small fiber neuropathy.

It has been demonstrated previously that patients biased toward an abnormal sensory test result cannot be distinguished from individuals with abnormal sensory function.19,20 Many of our patients with normal skin biopsies were referred to “rule out” small fiber neuropathy, because they believed they had a diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. The similarities across symptom and examination scores in our groups of subjects may be related to this potential bias in the normal skin biopsy group. However, more detailed investigation into potential bias in a larger number of subjects is needed to answer these questions.

Only a minority of patients had definite small fiber neuropathy on skin biopsy, and an additional 13% had a diagnosis of borderline SFN. This is likely related to the selection bias noted by the referring physicians, as many patients were referred to “rule out” rather than “rule in” the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy.

A small group of individuals with normal IENFD had morphological changes, such as nerve fiber swellings and were placed in the borderline small fiber neuropathy group. The morphologic changes may indicate an early or ongoing process affecting small fibers that precedes a decrease in IENFD.2,7 These patients may benefit from a follow-up skin biopsy to assess for progression or resolution of disease. We did not have sufficient numbers of patients to determine the utility of repeated skin biopsies. Among those with a low pretest probability of small fiber neuropathy, a normal skin biopsy appeared to reduce expensive serological testing, although this was difficult to quantify given the limitations of our study.

Not surprisingly, patient comorbidities appeared to be a strong predictor of small fiber neuropathy on skin biopsy. Only 1 of 13 patients with a comorbid psychiatric disorder and no patients with fibromyalgia, migraine, chronic daily headache, chronic pain, or chronic fatigue showed evidence of small fiber neuropathy on skin biopsy. All patients with type I diabetes mellitus had evidence of small fiber neuropathy. However, patients with other diagnoses often associated with small fiber neuropathy including type II diabetes mellitus, Sjogren syndrome, and paraproteinemias had mixed biopsy results. Therefore, the presence of laboratory or clinical evidence of associated syndromes is not sufficient to confirm a small-fiber neuropathy.

Questions remain about the optimal number of skin biopsies needed for diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Most studies reported in the literature suggest 1–3 skin biopsy sites for diagnosis of SFN.5,14,17,21–23 However, clinical cases may present as ganglionopathy, non–length-dependent neuropathy, or distal small fiber neuropathy. The optimal number of biopsies in this scenario has not been established. In our cohort, we found 3 biopsies to be more useful diagnostically than 2 biopsies in >20% of cases, although it is not clear how often the performance of 3 biopsies rather than 2 led to a change in management. However, this was a small study, and this was not a primary endpoint. Further investigation into this question is needed, because in cases where only a distal small fiber neuropathy is suspected, it may be reasonable to consider only 1 or 2 biopsies for diagnosis. Our study had several limitations, including small size and retrospective analysis of data. In addition, we attempted to limit “change in management” data to that performed in reaction to biopsy results. However, in clinical practice, as many patients had already undergone extensive laboratory and imaging work-ups and had been referred by other specialists before or concurrently while undergoing small fiber neuropathy evaluation, our data may underestimate the extent to which skin biopsy streamlines the medical work-up for undiagnosed symptoms. In addition, division of study subjects into 3 groups reduced the power to detect differences in symptoms and examination findings between groups. Finally, we did not include patients with non–length-dependent small fiber neuropathy, a population in which pathologic confirmation of small fiber neuropathy would be especially helpful in making a diagnosis.22,24 A larger prospective study is necessary to confirm our findings.

REFERENCES

1. Polydefkis M, Hauer P, Griffin JW, McArthur JC. Skin biopsy as a tool to assess distal small fiber innervation in diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Technol Ther 2001;3:23–28.

2. Gibbons CH, Griffin JW, Polydefkis M, Bonyhay I, Brown A, Hauer PE, et al. The utility of skin biopsy for prediction of progression in suspected small fiber neuropathy. Neurology 2006;66:256–258.

3. Griffin JW, McArthur JC, Polydefkis M. Assessment of cutaneous innervation by skin biopsies. Curr Opin Neurol 2001;14:655–659.

4. McArthur JC, Griffin JW. Another tool for the neurologist’s toolbox. Ann Neurol 2005;57:163–167.

5. Lauria G, Bakkers M, Schmitz C, Lombardi R, Penza P, Devigili G, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density at the distal leg: a worldwide normative reference study. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2010;15:202–207.

6. Lauria G, Hsieh ST, Johansson O, Kennedy WR, Leger JM, Mellgren SI, et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:903–912.

7. Lauria G, Morbin M, Lombardi R, Borgna M, Mazzoleni G, Sghirlanzoni A, et al. Axonal swellings predict the degeneration of epidermal nerve fibers in painful neuropathies. Neurology 2003;61:631–636.

8. Vlckova-Moravcova E, Bednarik J, Belobradkova J, Sommer C. Smallfibre involvement in diabetic patients with neuropathic foot pain. Diabet Med 2008;25:692–699.

9. Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, Camozzi F, Lombardi R, Melli G, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain 2008;131:1912–1925.

10. Lacomis D. Small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2002;26:173–188.

11. Scherens A, Maier C, Haussleiter IS, Schwenkreis P, Vlckova-Moravcova E, et al. Painful or painless lower limb dysesthesias are highly predictive of peripheral neuropathy: comparison of different diagnostic modalities. Eur J Pain 2009;13:711–718.

12. Lauria G, Cornblath DR, Johansson O, McArthur JC, Mellgren SI, Nolano M, et al. EFNS guidelines on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol 2005;12:747–758.

13. Dabby R, Vaknine H, Gilad R, Djaldetti R, Sadeh M. Evaluation of cutaneous autonomic innervation in idiopathic sensory small-fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2007;12:98–101.

14. Walk D, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Davey C, Kennedy WR. Concordance between epidermal nerve fiber density and sensory examination in patients with symptoms of idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. J Neurol Sci 2007;255:23–26.

15. Lauria G, Lombardi R, Camozzi F, Devigili G. Skin biopsy for the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Histopathology 2009;54:273–285.

16. Uceyler N, Kafke W, Riediger N, He L, Necula G, Toyka KV, et al. Elevated proinflammatory cytokine expression in affected skin in small fiber neuropathy. Neurology 2010;74:1806–1813.

17. Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy: a reversible painful autonomic neuropathy. Ann Neurol 2010;67:534– 541.

19. Dyck PJ, Kennedy WR, Kesserwani H, Kesserwani H, Melanson M, Ochoa J, et al. Limitations of quantitative sensory testing when patients are biased toward a bad outcome. Neurology 1998;50:1213.

20. Freeman R, Chase KP, Risk MR. Quantitative sensory testing cannot differentiate simulated sensory loss from sensory neuropathy. Neurology 2003;60:465–470.

21. Lauria G, Devigili G. Skin biopsy as a diagnostic tool in peripheral neuropathy. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2007;3:546–557.

22. Gorson KC, Herrmann DN, Thiagarajan R, Brannagan TH, Chin RL, Kinsella LJ, et al. Non-length dependent small fibre neuropathy/ganglionopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:163–169.

23. Uceyler N, Devigili G, Toyka KV, Sommer C. Skin biopsy as an additional diagnostic tool in non-systemic vasculitic neuropathy. Acta Neuropathol 2010;120:109–116.

24. Gemignani F, Giovanelli M, Vitetta F, Santilli D, Bellanova MF, Brindani F, et al. Non-length dependent small fiber neuropathy. a prospective case series. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2010;15:57–62.